America’s 28 million small businesses account for over 50% of all sales and almost half of the jobs in the United States. The smallest of these businesses, known as micro-businesses, are places like your local coffee shop or hardware store. They are often started by entrepreneurs who want to be more self-sufficient and are driven to contribute to their community. But many entrepreneurs in low-income communities cannot access business credit from the mainstream financial system, often because their businesses are too new, their credit files are too thin, or the amounts of capital they request are too small to qualify for traditional bank loans. That’s where community development financial institutions (CDFIs) fill an important gap.

Take Carmen and Robert for example. Six years ago, in the midst of the Great Recession, Carmen and her husband Robert [not their real names] wanted to start a small business. They contemplated numerous ideas – a bar, a restaurant, a grocery store – but Robert still had a full time job at the time, so they needed a business that Carmen could manage on her own. Ultimately, they decided to open a clothing store. The primary reason? They wanted to revitalize their community.

“We ventured into retail and trying to bring back to the community what we don’t have. Trying to keep people in town. At that time gas prices were so high and just trying to keep people in town to purchase their goods was one of our main goals,” Carmen explains. With poor credit and little business experience, Carmen and Robert were having trouble getting the capital they needed to realize their vision, despite a strong business plan.

CDFIs, which include numerous nonprofit microenterprise lenders, generally support entrepreneurs like Carmen and Robert—people committed to working in their own communities, but often doing so at the edges of the economy. The CDFIs provide small amounts of capital and other business advice to people whose businesses may be young or who lack the financial or personal documentation required by mainstream lenders.

According to research from the Aspen Institute’s Microenterprise Fund for Innovation, Effectiveness, Learning, and Dissemination (FIELD) the majority of microfinance clients in the U.S. (>70% on average) are women, people of color, and/or individuals living at or below the median income in their community. While there is a healthy amount of financial data on these loans, little is known about the impact that microenterprise loans have on the lives of business owners and their households, their businesses, and their communities.

Going beyond financial metrics to understand impact

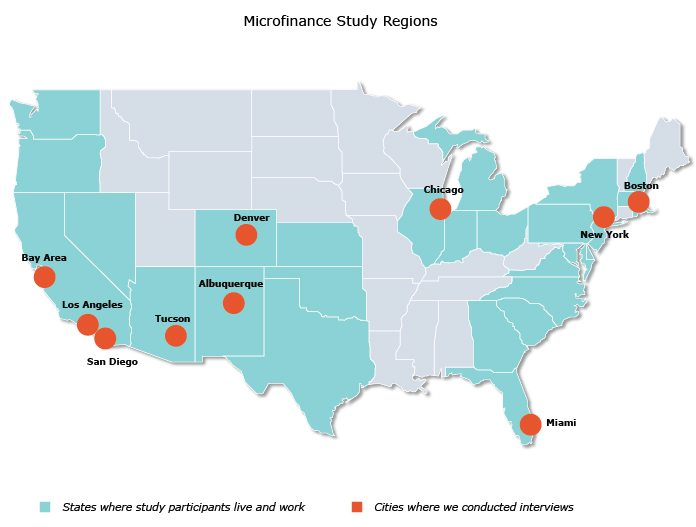

To address this gap in knowledge, in 2015, the Accion U.S. Network and Opportunity Fund, two of the nation’s leading nonprofit microenterprise lenders, partnered with Harder+Company Community Research to launch a first-of-its-kind, longitudinal, national study to gain new understanding of the impact of their lending services on borrowers across the nation. This study expands on past microfinance evaluations by looking more deeply at the holistic, long-term impacts of these loans and business advising. We are doing this by following a cohort of more than 500 borrowers in 21 states across the country to understand how these small business owners define success beyond their balance sheets, and how access to capital improves their entrepreneurial goals, financial health, and quality of life.

The national scope of this study allows us to consider variations in impact depending on business type, geography, and other factors. Our study findings will deepen the field’s understanding of how mission-based business lending impacts individual entrepreneurs and their families, their businesses, and their communities.

As we begin the second phase of data collection, we have already learned some important things about these entrepreneurs and the impact of Accion and Opportunity Fund (you can find our baseline report and a summary here, and sign up for updates here).

- Accion and Opportunity Fund are supporting marginalized populations. Most of their borrowers come from families that can’t afford to invest in their ventures. Many are starting a business for the first time. Many are immigrants or second generation immigrants. Some don’t speak English. Most – 73% – are low income.

- Entrepreneurs report working long hours to start or sustain their business, and some still have to work a second job. But they also report feeling greater control after obtaining a loan from Accion or Opportunity Fund and greater flexibility over their schedules, which allows them to spend more time with family.

- Entrepreneurs do not always have a place to turn to (e.g., savings, family, other lending institutions) during financial emergencies and most do not have financial plans to support their growth.

- Business owners report many benefits from the services they receive from Accion and Opportunity Fund and feel especially supported in strengthening their business practices, such as financial tracking and sales projection.

As for Carmen and Robert, they attribute their current business success to Opportunity Fund. Without that small but significant loan, they say they wouldn’t be where they currently are. After securing a storefront at a local mall – many of which were vacant during the Great Recession – they have expanded to two more locations, have hired three additional employees, and continue to thrive in their business. But while Carmen and Robert have already experienced gains in business growth, they, like many of those in the study, still face significant challenges, including limited cash flow or savings to address unexpected costs, and inadequate capital to meet rising costs.

- We stay flexible to account for cultural diversity: We knew we’d have to account for multiple languages, ethnicities, and cultural practices, but we also changed our outreach to account for different types of businesses and communities. Entrepreneurs ranged in education, level of business knowledge, and complexity of their business structure. Moving between interviewing a hot-dog cart owner in Los Angeles in Spanish to a speech pathology consultant in English in Denver takes flexibility and humility. To account for this diversity, we took a more ethnographic and human-centered approach, inviting entrepreneurs to tell us about their lives and businesses before diving into more targeted questions.

- We use technology strategically: Technology tools like online surveys and scheduling platforms make it easier to collect high volumes of data from study participants, but may not be the best tool for certain populations. We made strategic use of technology by staggering our data collection – first launching an online survey, then following up with phone calls and mailed surveys to meet our sampling criteria. Similarly with interviews, we launched online scheduling first, and then focused on more targeted outreach of entrepreneur categories that weren’t going to be as accessible by email.

- We stay connected between data collection moments: We used marketing tools (e.g., we sent a happy New Year e-mail and post card) to remind entrepreneurs of the study. With a longitudinal study, it is imperative that participants stay engaged to reduce attrition. Continuous engagement also allowed us to track changes in contact information of the entrepreneurs participating in the study.

By going beyond existing indicators, this study is starting to show the broader impact that micro loans have on individual entrepreneurs and their households, businesses, and communities. Our future data collection will focus on tracking how lending services impact the economic security and financial goals of individual entrepreneurs, the commercial viability of the businesses funded by micro loans, and entrepreneurs’ engagement in and relationship to their local communities. We will have final results to share in early 2018.